If history shows us anything, it’s that, for millennia, people have been making alcohol out of whatever random plant materials are close to hand – even from the most unlikely-looking sources. Take the agave: tough, sharp and spiky, it’s the kind of scary-looking specimen you’d give a wide berth if you encountered it on a hike.

And yet, some bright spark (likely an enterprising Aztec Indian, circa 250 A.D.) not only considered it a candidate for recreational fermentation but also took the time to work out which of the hundreds of species contained enough sugar to be turned into alcohol.

Tapping into history

The evolution of modern-day tequila is an interesting story. Its origins lie in a sticky, kombucha-style, ceremonial ‘pulque’ made from raw agave sap in pre-Hispanic Mexico and thought to be a gift from the gods.

When the Spanish conquistadores arrived in the early sixteenth century, along with their knowledge of advanced distillation techniques and a thirst for more sophisticated spirits, they spurned the local brew and began experimenting with ‘mezcal wine’ – the progenitor of tequila – from the cooked, fermented juice of the plant.

In the same way that all thumbs are fingers but not all fingers are thumbs, all tequila is mezcal but not all mezcal is tequila.

Both are made from the cooked, fermented and distilled hearts of the agave (piñas), admittedly using slightly different methods. But while mezcal* can be made from any species of agave, tequila – named after an agave-wine-producing town west of Guadalajara – uses only the blue agave, while its Appellation of Origin (AOC) also means it can only be made in a handful of regions in Mexico.

Baked-in flavour

In traditional distilleries, masonry ovens, called ‘hornos’, are still used to cook the agave hearts before being shredded and fermented in copper stills, although more modern stainless-steel autoclaves and stills have become commonplace, with some large-scale manufacturers controversially shifting production methods to a no-bake diffusor-extraction model.

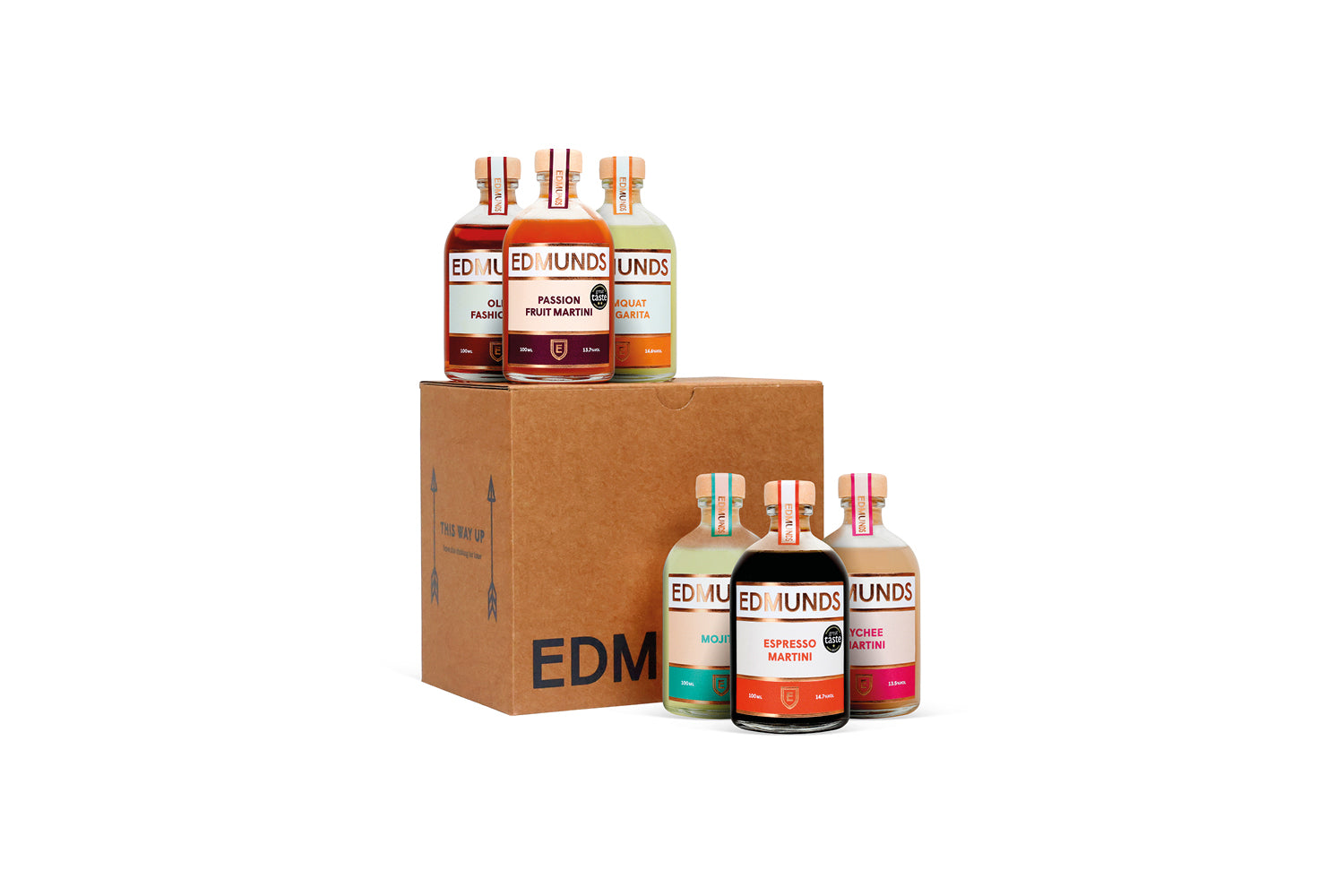

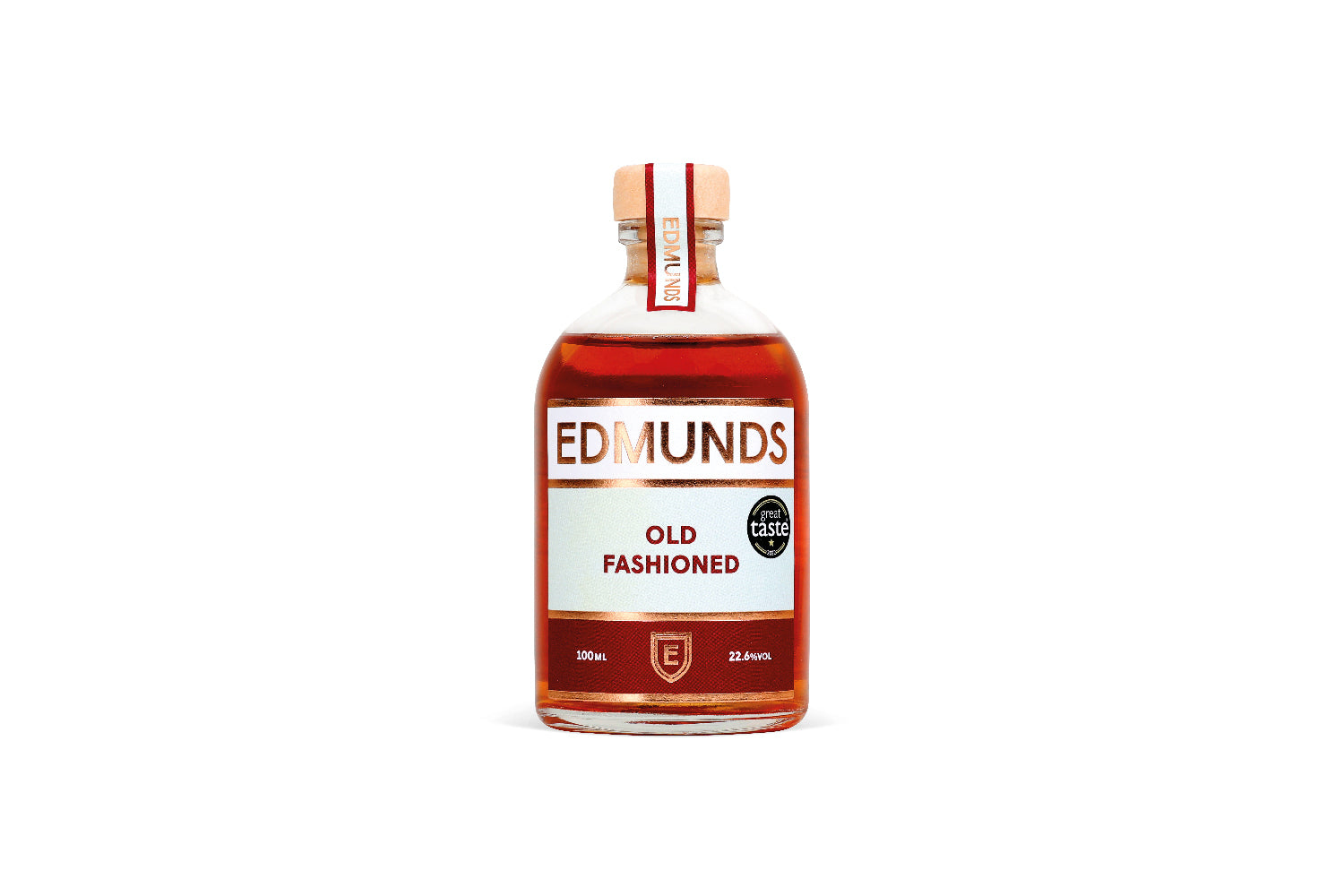

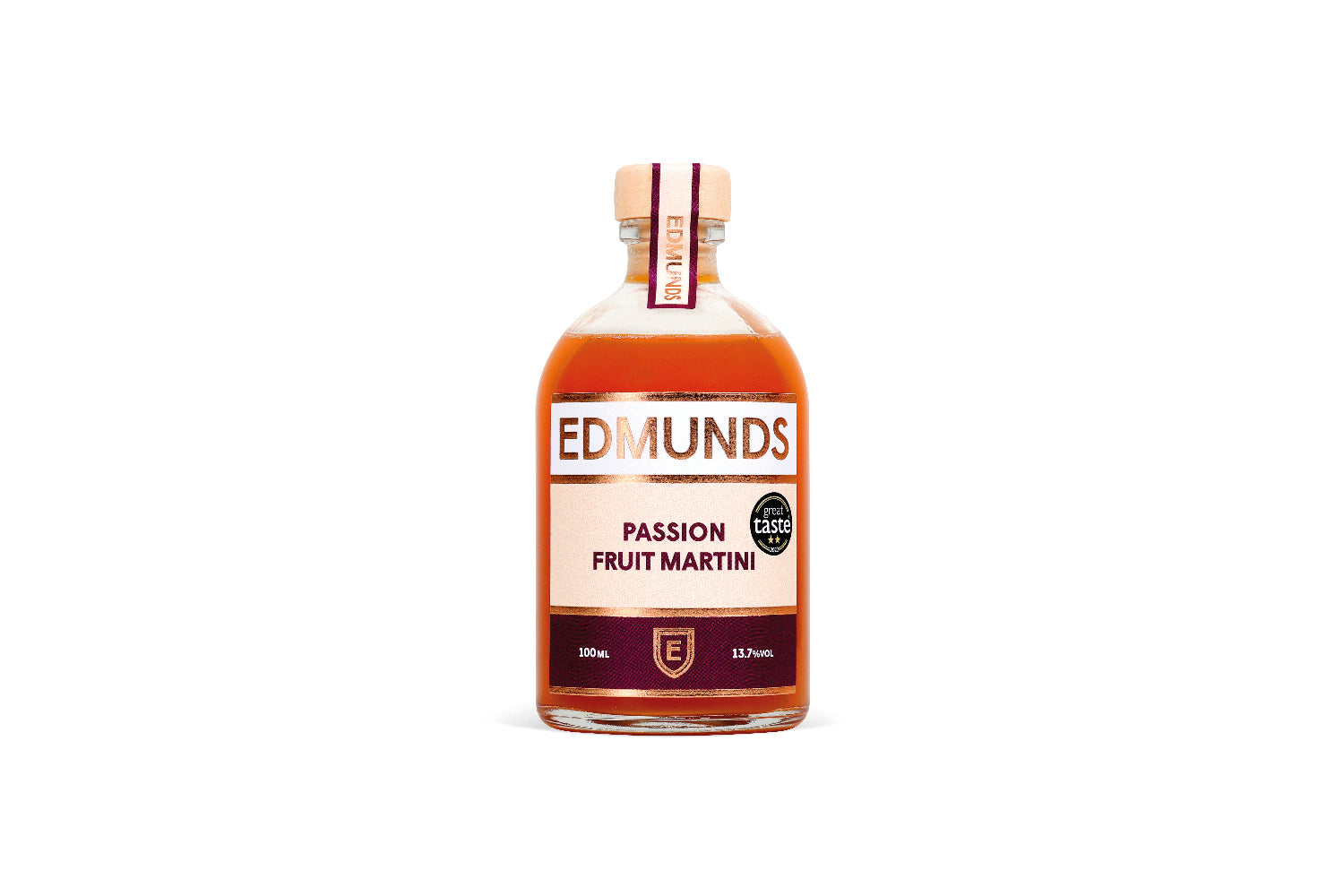

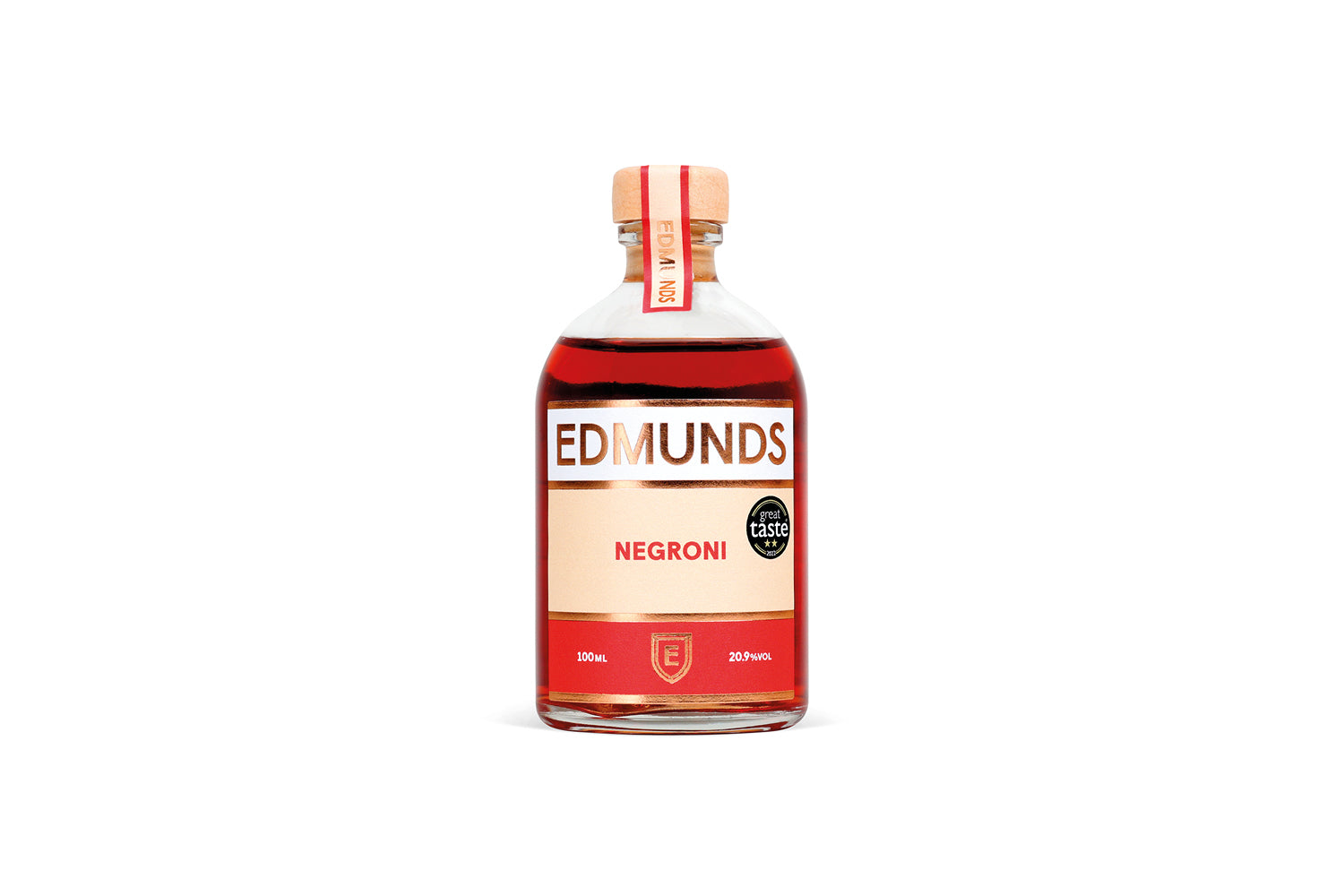

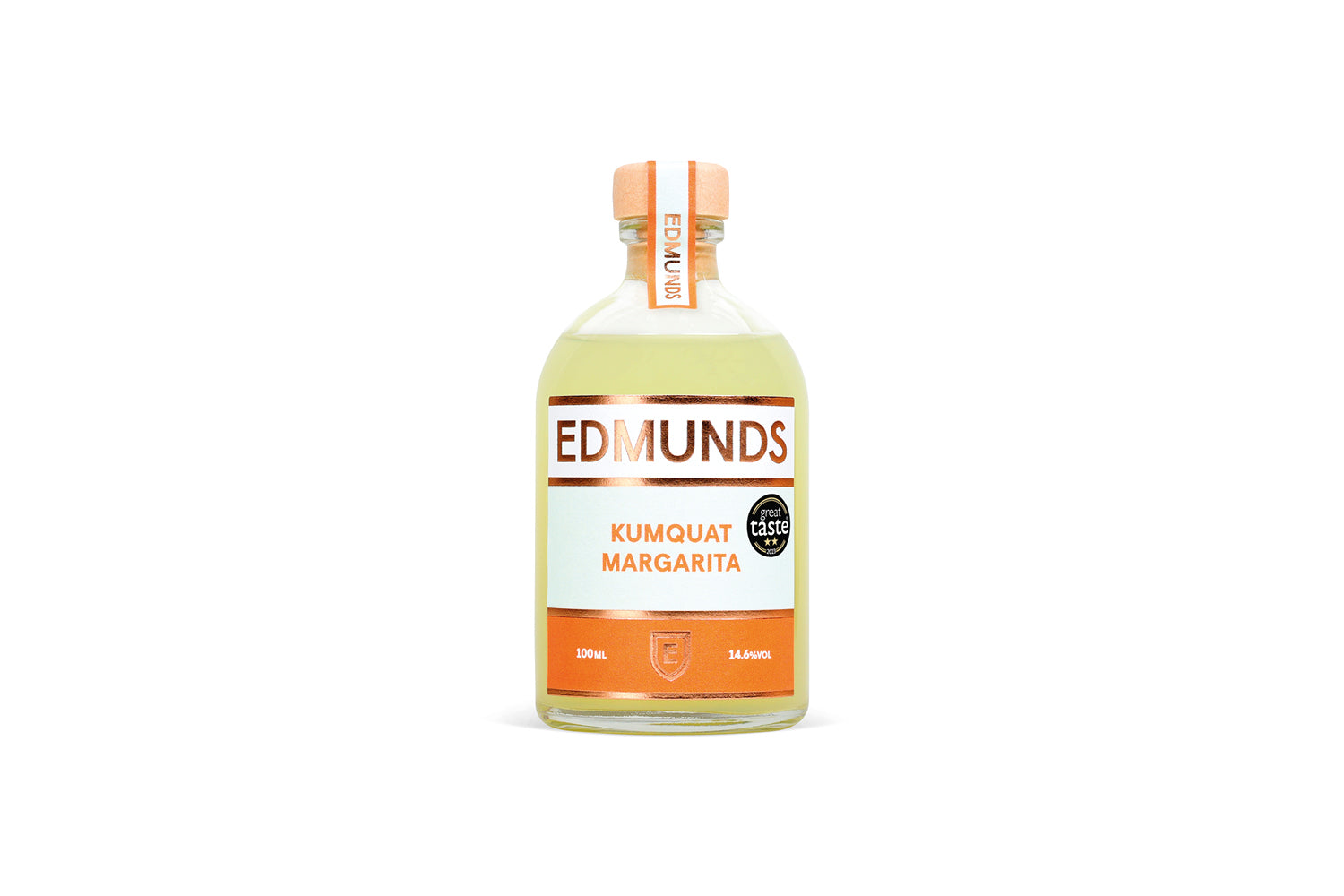

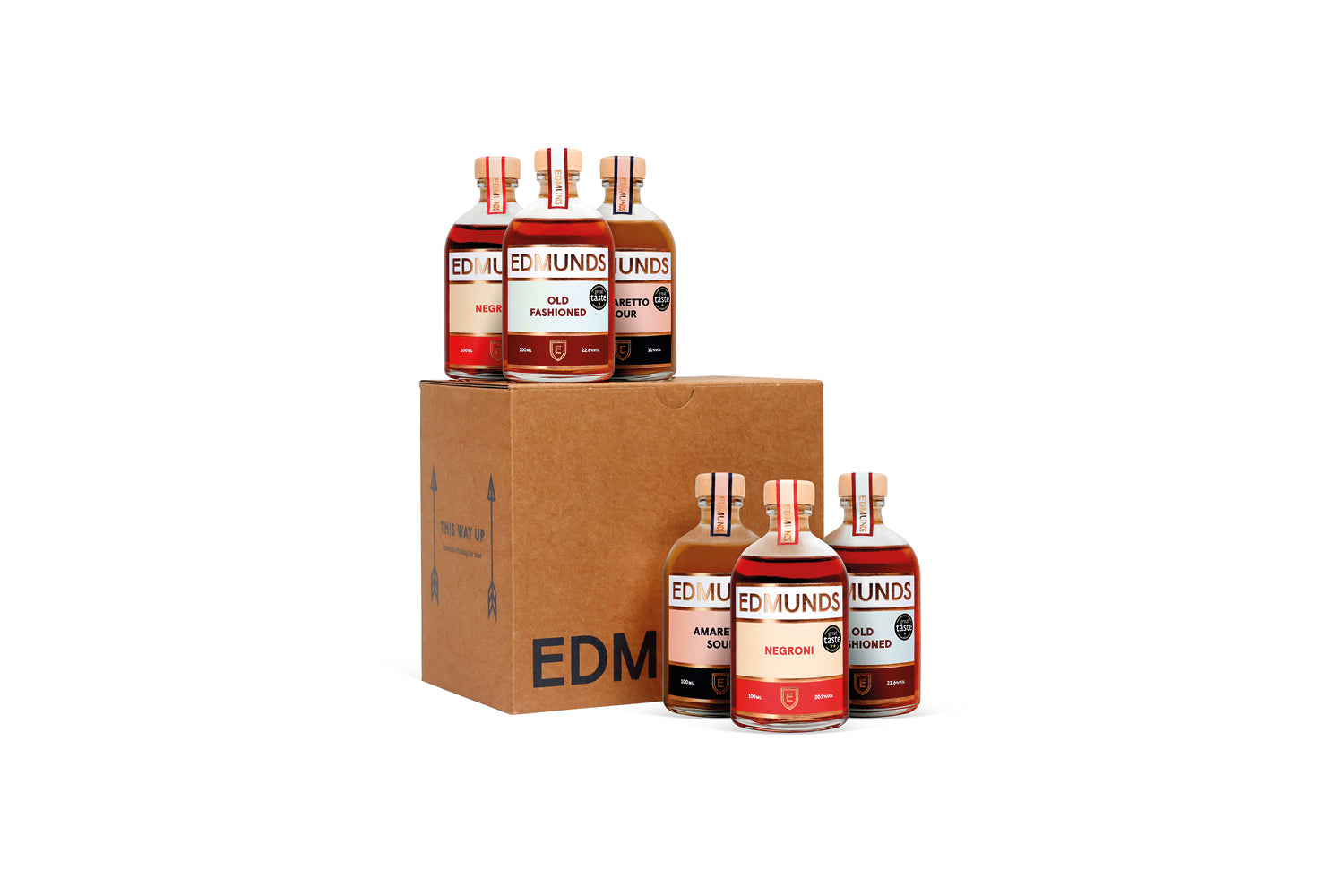

Premium tequila brands (like the one used by Edmunds – El Rayo) tend to be made from 100 per cent blue agave and are bottled in the region of their production; those that include added cane or corn sugar prior to fermentation are known as ‘mixto’. Tequila is sold in unaged, colourless ‘silver’ or ‘blanco’ varieties, as well as reposado (rested) and añejo (old) styles, whose caramel spectrum reflects various stages of the oak-cask ageing process.

Mixing it up

In Mexico, tequila is most often served as a neat shot accompanied by a fruit-based chaser – known as a sangrita – that’s a blend of orange, pomegranate and lime juices with a dash of hot chilli sauce. When it comes to tequila-based cocktails, though, there are plenty of classics to fire the imagination, including the iconic Margarita, highball-style Ranch Water and the ultimate-go-to-drink-for-an-instant-beach-holiday-vibe, the Tequila Sunrise.

Perhaps the most popular tequila-based cocktail on its own turf, though, is the Paloma (dove) – reputedly the creation of legendary Mexican bartender Don Javier Delgado Corona. Best thought of as Margarita’s sparkling cousin, the Paloma offers a refreshing brunch-style experience that can be enjoyed anywhere.

At Edmunds, our take on the Paloma uses premium El Rayo tequila made with 100 per cent blue agave and water, imparting the sweet/tart flavour of grapefruit to a classic tequila-and-lime partnership, with a little agave nectar for sweetness. Simply pour over ice and top with soda water (or grapefruit soda) before serving. We think it’s a summer fixture everyone can get behind. Salud!

*If the idea of finding a worm in your tequila gives you the ick (as well it should), it’s reassuring to know that the Tequila Regulatory Council doesn’t allow crawlies of any kind to be added to tequila bottles. In fact, only certain mezcals were ever sold ‘con gusano’ (with a worm) and only ever as a gimmick. So that’s cleared that up.